Norpace

Asheesh, Bedi, MD

- Assistant Professor, Sports Medicine and Shoulder Surgery,

- Medsports, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

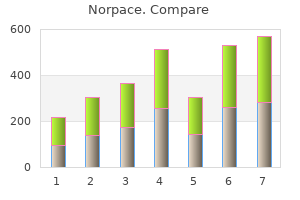

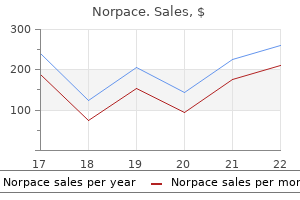

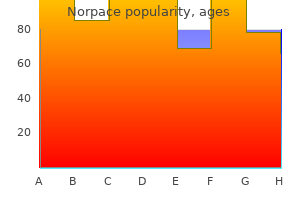

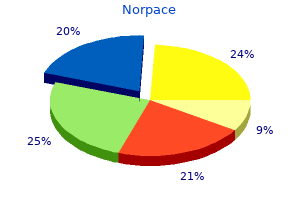

Furthermore medications used to treat adhd generic norpace 150mg free shipping, stenting generally requires the lifelong use of dual antiplatelet medications medicine bow wyoming order norpace cheap online, and various complications treatment 1st metatarsal fracture purchase cheap norpace line, including in-stent stenosis or thrombosis and periprocedural hemorrhage medicine 4h2 buy norpace 150 mg cheap, have been reported conventional medicine buy cheapest norpace and norpace. In these cases medicine xalatan order generic norpace pills, surgical bypass, with the option of performing multiple bypasses as needed, may still be the preferred method of treatment. These are also problematic in that they often incorporate multiple branching arteries. Although various attempts have been made to revascularize multiple branches and either isolate or proximally occlude the aneurysm segment, the results for these complex lesions are often inadequate, and devastating complications with treatment. These represent a very difficult pathology with a poor natural course and do not generally respond well to any treatment type. The most common tumor types that present this surgical challenge are meningiomas, schwannomas, pituitary adenomas, angiofibromas, and chordomas. Because of the benign nature of these tumor types, the carotid is most frequently partially or completely encased by tumor rather than invaded. In these cases, complete resection is not possible unless the carotid artery is resected along with the tumor, with or without a revasculariztion procedure. Malignant skull base and head and neck tumors are more likely to invade the vessel. In these cases, radical oncologic resection, if that is an appropriate goal, may require carotid occlusion and resection. Additionally, stereotactic radiosurgery is an effective strategy to treat tumors of the skull base with less likelihood of injury to neurovascular structures. Benign tumors, such as meningiomas and schwannomas, are often very sensitive to radiation treatment. There is therefore a growing consensus that the carotid artery should not be resected for most nonmalignant tumors. The high rate of morbidity related to carotid artery sacrifice alone, without bypass, and the modest rate of morbidity associated with balloon test occlusion suggest that selective revascularization should be considered when artery resection is deemed essential to achieve an oncologically meaningful resection. If bypass is deemed necessary in the management of a skull base tumor, the revascularization procedure can be done as a separate, preliminary, staged procedure or at the same time as the tumor resection. Complications related to the balloon test occlusion procedure alone can occur in approximately 3% of patients. Bilateral vertebral artery or basilar artery occlusion is associated with a much higher risk for ischemia and should be considered only if blood flow through both posterior communicating arteries is sufficient (<1 mm). Typically, patients are given standard anticonvulsants when a cerebral hemisphere is to be exposed or retracted. Preoperatively, all patients are given aspirin (325 mg daily) to minimize the risk for postoperative thrombosis and occlusion at the anastomotic site. Evoked potential monitoring reflects the activity of the sensory cortex and subcortical and brainstem pathways during bypass procedures. The efficacy of barbiturates for cerebral protection during transient focal ischemia is supported most strongly by laboratory and clinical evidence. The combination of preoperative aspirin, mild hypothermia, and system heparin administration causes a problematic degree of intraoperative and postoperative coagulopathy. The bypass donor and recipient vessels are simply flushed and the anastomosis irrigated with heparinized saline. Proximal occlusion of this artery for giant or fusiform arteries is usually well tolerated; only a few cases develop an ischemic deficit (hemianopsia). The primary example of this type of revascularization is the purely intracranial petrous carotid-supraclinoid carotid saphenous vein interposition graft. It is used primarily to reconstruct the carotid artery when it must be resected to remove skull base tumors and to treat giant intracavernous carotid aneurysms. It is associated with a significant complication rate related to graft occlusion and perioperative Distal Arterial Branches In general, occlusion of distal arterial branches without considerable collateral circulation is associated with a substantial risk for ischemia and infarction. Revascularization of these terminal branches should be considered when these vessels must be occluded. Despite these advantages, a vein graft generally has lower long-term patency rates and a higher risk for kinking, and there can be problems with caliber mismatch between the larger vein and smaller intracranial vessels. Alternatively, a radial artery graft can be used, which has a smaller diameter (about 3. A petrous-supraclinoid carotid skull base bypass showing a saphenous interposition graft from the petrous segment of the carotid artery (exposed by drilling the middle cranial fossa floor) to the supraclinoid carotid artery (in this case for treatment of an intracavernous aneurysm). Petrous carotid-to-intradural carotid saphenous vein graft for intracavernous giant aneurysm, tumor, and occlusive disease. A, Preoperative magnetic resonance image shows squamous cell carcinoma involving the orbit and cavernous sinus (arrows). B, Carotid angiogram after resection of the orbital and cavernous sinus contents (including the involved carotid artery) shows a type I saphenous vein graft (between arrows) from the petrous to the supraclinoid carotid artery. A, A clamp is passed from the cranial incision behind the root of the zygomatic arch to the cervical incision. C, the harvested saphenous vein graft is passed through the chest tube, which is removed leaving the graft in its subcutaneous tunnel. With excessive retrograde filling from a robust saphenous vein graft, the aneurysm can remain patent, continue to enlarge, or even rupture in some cases. After the carotid bifurcation is exposed and a pterional craniotomy opened, the sylvian fissure is opened widely. The ideal M2 or M3 arterial recipient site, free of perforating vessels, is exposed. Next, the saphenous vein is exposed and isolated but left in situ in continuity until just before it is used for the bypass. Meticulous care is exerted while exposing the vein to avoid trauma that might cause the bypass to thrombose. The vein is ligated proximally and distally, excised, and flushed without overdistention with cool, heparinized saline. Blunt dissection with a clamp is used to create a subcutaneous tunnel from the cranial incision behind the root of the zygomatic arch to the cervical incision. The orientation of the vein is observed carefully to keep it from twisting as it is passed through the tube. The chest tube is then pulled from the cervical incision to the cranial incision with a clamp. The graft is filled with cool, heparinized saline and occluded proximally and distally with temporary clips. As suggested by Sundt and associates,5 the intracranial anastomosis is performed first. This sequence allows the surgeon to take advantage of slack in the graft, which can be manipulated freely while the back and front walls of the anastomosis are sutured. The terminal 5- to 6-mm portion of the vein graft is trimmed of loose adventitia, and the end is beveled to create an orifice 5 to 6 mm in diameter. After the anastomosis is completed, blood flow is restored, and the barbiturates can be stopped. The vein graft is pulled gently into the cervical incision to remove slack and redundancy. Following removal of the temporary occluding clips, if the proximal and distal anastomoses are widely patent, a bounding pulse should be visible and palpable in the vein graft. If there is any doubt about the integrity of the graft, intraoperative angiography should be considered. The craniotomy is closed with care to avoid compromising the vein graft with dura or temporalis muscle. Closure of the lateral or "front" wall of the anastomosis is facilitated by bringing the vein under the blade of the self-retaining retractor on the temporal lobe. Sundt and coworkers5 observed that a large percentage of patients develop subdural hygromas after this procedure. They suggested routinely placing a subtemporal subdural-peritoneal (or atrial) shunt to avoid this complication. This procedure is used when a giant aneurysm requires occlusion of a single, crucial arterial branch or when carotid occlusion is required (for an aneurysm or tumor) and the circle of Willis is only marginally inadequate. These grafts are generally readily available, only require a single anastomosis, and have good patency rates compared with free vein or arterial grafts. The occipital artery has a similar caliber and flow rate but is marginally more difficult to harvest and anastomose. Cerebrospinal fluid is drained through a lumbar subarachnoid catheter to relax the brain enough to elevate the temporal lobe safely. The proximal 20 to 25 mm of the P2 segment is isolated, and a segment free of brainstem perforating vessels is chosen for the anastomosis. The artery is exposed to the zygomatic arch, separated from the adjacent subcutaneous tissue with an adventitial cuff, and left in continuity until detached for anastomosis. C, After the temporalis muscle is incised, an oval or circular craniotomy is made over the posterior aspect of the sylvian fissure. Anterior and posterior temporal muscle flaps are developed, and a small oval craniotomy flap is made. After the dura is opened and an appropriate recipient artery (1 mm diameter) is selected, the arachnoid over this vessel is opened, and a 10-mm length of the vessel is prepared. A, Magnetic resonance image shows a large aneurysm within the left sylvian fissure. C, the aneurysm is trapped, and the angular branch was occluded as it exited the aneurysm. The dura is reapproximated loosely, the bone flap is trimmed to leave an opening for the bypass vessel, and the temporalis muscle is closed loosely. The sterile Doppler probe is employed periodically to ensure that bypass flow is not compromised during the closure. A hockey stick incision, with the transverse limb located 1 cm above the superior nuchal line, is made. The occipital artery is dissected from the subcutaneous tissue and suboccipital musculature. After initial exposure of the occipital artery at the nuchal line, it is dissected from the undersurface of the myocutaneous suboccipital flap, which is retracted laterally. The vessel is left in continuity until just before it is required for the anastomosis. A multilayer meticulous muscle closure is essential because a watertight dural closure cannot be achieved. During the muscle closure, the occipital artery must not become kinked or severely compressed under the suboccipital muscles. An unbranched length of the recipient vessel is isolated and occluded after barbiturates are administered. C, Late phase of the external carotid injection shows bypass filling a significant volume of the cerebellar hemisphere circulation. They are also useful for deep recipient locations, such as the interhemispheric pericallosal-pericallosal bypass, which is difficult to reach with scalp or harvested grafts. Clearly, further experience with these types of procedures is needed to fully evaluate their potential advantages compared with more traditional forms of revascularization. Technique for pericallosal artery-pericallosal artery intracranial revascularization. The arteries are exposed adjacent to the corpus callosum, and a side-to-side anastomosis is made. B, An example of a completed pericallosal artery-pericallosal artery bypass for the treatment of a giant, wide neck, partially thrombosed anterior communicating artery aneurysm (arrow). Complete occlusion of the aneurysm required anterior communicating artery occlusion. The bypass was required to reconstruct a new "communicating artery" because the contralateral A1 segment was atretic. PrimaryReanastomosis the simplest form of intracranial arterial reconstruction involves aneurysm excision with primary reconstruction of the parent artery. This procedure is possible only when the excised segment of the parent artery is short and the remaining proximal and distal segments of the vessel are redundant enough to allow tensionfree primary reanastomosis. The two distal vertical midline segments are approximated and occluded proximally and distally after burst suppression has been achieved. The side-toside anastomosis is performed as described for the pericallosalpericallosal anastomosis. After barbiturates are administered, temporary clips are placed on each pericallosal artery just beyond the genu of the corpus callosum. A 5-mm linear arteriotomy is made along the medial surface of each pericallosal artery. The back walls of the two pericallosal arteries are joined first with running 10-0 nylon suture, followed by closure of the front wall with a second suture. On the back wall, careful planning is required to place the suture so that the knot ends up outside the lumen. Techniques for Occluding or Trapping an Aneurysm after Bypass It is often possible to occlude an aneurysm surgically by trapping it (combined proximal and distal parent artery occlusion) immediately after the bypass is completed. Trapping is preferable because it isolates the aneurysm from the circulation, avoids the risk for rupture from retrograde filling (reported in rare cases), and allows immediate decompression of the aneurysm to relieve mass effect. Proximal parent artery occlusion alone, which alters the blood flow to the aneurysm, tends to be adequate to induce aneurysmal thrombosis. Direct surgical occlusion of the proximal parent artery in the neck or just proximal to the aneurysm is typically performed immediately after construction of the bypass. In such cases, balloon or coil occlusion of the parent artery shortly following bypass can be used.

The vessel dilation can cause turbulence symptoms joint pain and tiredness discount 150 mg norpace mastercard, damage to branching vessels treatment 6th nerve palsy buy discount norpace 100 mg on-line, and thrombus formation medications used for migraines cheap norpace 150 mg fast delivery. Some fusiform aneurysms treatment borderline personality disorder purchase generic norpace on line, however medications pictures generic 100 mg norpace with mastercard, require occlusion-for example symptoms 0f pneumonia purchase norpace without prescription, if growth occurs, causing symptoms through compression, or if rupture occurs. Despite advances in surgical and endovascular techniques, fusiform aneurysms remain a therapeutic challenge. Instead, fusiform aneurysms of the vertebral artery may be best treated with endovascular hunterian ligation under full heparinization or by surgical hunterian ligation when precise ligation is necessary to prevent inclusion of vital perforators. In addition, they are fragile and have a propensity to rupture during manipulation. Short-term angiographic follow-up suggests that bipolar electrocoagulation and reinforcement with muslin gauze (or clip wrapping) may be a reasonable option in some patients. This poor prognosis warrants aggressive management, preferably in tertiary referral centers. However, despite advances in microsurgery and the development of new endovascular techniques, the treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms remains a challenge. However, surgical results by direct clipping for giant aneurysms are worse than for small aneurysms even when using sophisticated techniques such as bypass or cardiac standstill. Hence revascularization and bypass surgery (extracranial to intracranial or intracranial to intracranial) often play an important role. However, they are more difficult to perform and two vessels rather than one vessel require temporary occlusion, so more tissue is at risk for ischemia. For giant anterior circulation aneurysms, an orbitozygomatic approach may be preferable to the pterional approach. For posterior circulation aneurysms, exposures such as the orbitozygomatic, various transpetrosal approaches (retrolabyrinthine, presigmoid, translabyrinthine, or transcochlear), the far lateral or extreme lateral approach, or a combination of approaches depending on aneurysm location may be needed. An orbitozygomatic approach is reasonable for lesions involving the upper two fifths of the basilar artery. For lesions involving the middle fifth, transpetrosal approaches are preferable, whereas far or extreme lateral approaches are suitable for aneurysms of the lower two fifths of the basilar artery and the intradural vertebral artery. When the lesion straddles these zones, a combination of approaches is recommended. Proximal and distal vascular control is important during repair of giant aneurysms; it permits reduction of aneurysm size and so improves visualization of the surrounding anatomy. Similarly, an aneurysm with intraluminal thrombosis can be opened and the clot removed. Surgical aneurysm clipping requires a favorable neck; many giant aneurysms have wide necks, whereas fusiform aneurysms have no intervening neck. Single clips may be inadequate; instead, several shorter clips or fenestrated clips placed serially along the aneurysm neck may be a better choice. These lesions are considered "benign," but treatment often needs to be considered when these aneurysms are large, erode the skull base. When direct surgery is considered, exposure of the carotid artery in the neck is necessary. Often carotid occlusion followed by additional cerebral bypass is needed for those patients who fail a balloon test occlusion. In addition, parent artery occlusion in these patients is associated with a greater rate of complete occlusion and lower retreatment rates. Anecdotal reports suggest that the collaboration between neurosurgeons and endovascular surgeons (or interventional neuroradiologists) will increase the number of patients who can safely be treated either de novo or after one technique fails. In large part this depends on the aneurysm morphology, aneurysm location, and patient health. For example, in a systematic review of the literature that included 82 studies comprising 90 patient cohorts, each with more than 50 patients, Rezek and colleagues379 found that coil type. These flow diverters are increasingly used in the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms, particularly complex aneurysms. Whereas some residual aneurysms may thrombose, even small residual aneurysms may regrow and bleed. Overall the incidence of rebleeding from residual ruptured aneurysms is estimated to be less than 0. However, aneurysms with broad-based residua frequently enlarge and appear to have a nearly fourfold greater risk of subsequent hemorrhage. Small residual dog-ears may be observed; however, careful long-term follow-up is important. How to manage the residual aneurysm after endovascular coiling is discussed later in this chapter. This outcome benefit is less evident at long-term follow-up, however, and depends in part on patient age. The selection of one treatment over the other requires a careful consideration of both patient- and aneurysm-specific factors. This recurrence may be seen in both partially and completely occluded aneurysms after coil embolization. Among the 665 aneurysms in 558 patients treated during the last 6 years, small aneurysms (4-10 mm in diameter) with small necks (<4 mm) had a 1. In large aneurysms (11-25 mm in diameter), recurrence was 30% in completely occluded aneurysms and 44% in incompletely coiled aneurysms. Sixty percent of incompletely occluded giant aneurysms (>25 mm in diameter) and 42% of completely occluded giant aneurysms recurred. Naggara and colleagues390 performed a recent systematic analysis of 71 publications between 2003 and 2008 describing endovascular treatment of aneurysms. The rate of occlusion and durability of occlusion can be increased with high-porosity stents, but this is associated with a higher risk of periprocedural complications. Failure to achieve complete occlusion and recurrence rates seem to be closely related to aneurysm morphology; in particular, large aneurysms (>10 mm) and posterior circulation aneurysms seem to recur more frequently because of coil compaction. Endovascular re-treatment (and its potential risks at each treatment) may not always negate the early benefit of endovascular techniques but needs to be considered when deciding upon a primary treatment strategy. Of these, 13 were from the originally repaired aneurysm, 10 of which initially had endovascular treatment and 3 of which had surgery. For example, Lempert and coworkers410 observed that 33% of giant aneurysms, 4% of large aneurysms, and no small aneurysms had new hemorrhage during an average of 3. Rerupture appears to be more common in the first year,114,115,374,402,408,411 and mortality is frequent with rerupture. For example, Sluzewski and van Rooij observed, among 431 patients who had a ruptured aneurysm coiled, that all patients who rebled died. Consequently, parent vessel reconstruction is preferred when appropriate, or surgery is advocated in some young patients. Overall, the published data suggest that complete endovascular occlusion is protective and that regrowth and rebleeding are frequent if not inevitable consequences of incomplete aneurysm occlusion. However, if only a 6-month postprocedure angiogram is performed, approximately half the aneurysm recurrences will be missed; therefore, regular follow-up angiography until at least 3 years after coil treatment is advisable. In the clipped aneurysm residual, the walls are closely apposed and the remaining aneurysm is completely excluded from the circulation. In addition, although experimental models of coiled aneurysms demonstrate that the aneurysm neck becomes entirely occluded by organized thrombus and that the free luminal surface is covered by endothelium,413,414 endothelialization is not observed in coiled aneurysms obtained at autopsy or surgery. Instead the aneurysm is separated from the vessel by a neointimal layer that often is thin and discontinuous. Patients with incompletely occluded coiled aneurysms consequently require repeat angiography, coil embolization, or surgery. Angiography is relatively safe in patients harboring cerebral aneurysms; less than 1% suffer a stroke. Important factors such as aneurysm location, degree of neck occlusion, chronicity since treatment, patient age and clinical condition, and reason for aneurysm recurrence can help in this decision. When treatment is indicated, repeat endovascular occlusion may be preferable when there is coil compaction with a resulting decrease in the volume of coils, whereas surgery may be preferable where there is aneurysm growth rather than coil compaction. However, morbidity with a flow diverter may be high if a stent is already in situ. Direct clip occlusion without coil manipulation is possible in about three quarters of cases, particularly if there is sufficient coil compaction to create a soft aneurysm neck, that is, there is sufficient space between the coils and the parent vessel for clip placement. Alternatively, a flow diverter may effectively treat the recurrent aneurysm, although the morbidity data are still high (>10%). Coil procedures appear less effective in large- or wide-necked aneurysms, particularly when considered relative to the aneurysm size. For example, Murayama and associates389 reported results for 916 aneurysms in 818 patients treated over 11 years and found that in small aneurysms (4-10 mm) with small necks (<4 mm), complete occlusion could be achieved in 75. Greater coil packing at the initial procedure may improve long-term aneurysm obliteration of large aneurysms but at the potential risk of increased complications at the time of procedure, particularly vessel occlusion or thromboembolism. Complete occlusion of incidental unruptured aneurysms using Guglielmi detachable coils (n = 120). Embolization of incidental cerebral aneurysms by using the Guglielmi detachable coil system. Aneurysm geometry, including aneurysm dome-to-neck ratio (maximum dome width/ maximum neck width), maximum neck width, and aspect ratio (dome height/maximum neck width) can help guide this decision. For example, superior hypophyseal aneurysms are more amenable to coils than carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms because the catheter tends to follow the curve of the siphon into the aneurysm because of its location within the concavity of the carotid artery. The advent of stents and flow diverters also has enhanced the ability to treat very small aneurysms, but this requires further study. For example, it is postulated that the likelihood of aneurysm recurrence after endovascular treatment may be further reduced with biologically active coils. With that has come a constant refinement in deciding which patient and which aneurysm, including the ruptured aneurysm, should be treated using microsurgical or endovascular techniques. Common sense suggests that one size does not fit all but rather decisions on technique should be on a case-by-case basis. With either technique, occlusion should be achieved as early as feasible to reduce the risk of rebleeding. The exception may be certain giant complex aneurysms, for which bypass techniques are needed. When using surgical techniques, greater complete aneurysm occlusion rates (90%) are achieved overall than when endovascular techniques (50%) are used. Despite the lower occlusion rates, observational series suggest that endovascular techniques provide protection against rebleeding in the first few months when rebleeding is most frequent. It is important that coiled aneurysms are followed over time because recurrent filling is seen in between 15% and 50% of aneurysms on angiograms obtained 6 months to several years after treatment. These rates are consistently higher than those in patients treated with surgery and therefore need to be considered in estimating total risk to the patient. However, the rates of complications of good- or poor-grade patients who have surgery for ruptured anterior circulation aneurysms are similar. Their data suggest that the outcome is similar independent of the technique of aneurysm occlusion; however, early treatment was associated with better clinical outcomes. Patients who undergo endovascular procedures often require anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents. Among 15 taking anticoagulants, 14 died or were dependent at 3-month follow-up, whereas 62 of the 126 patients not taking anticoagulants suffered a similar fate. It is uncertain whether these findings apply to short-term anticoagulation or to antiplatelet agent use. This is important because thromboembolic events appear to be the most common adverse events in endovascular procedures, with a reported incidence between 2% and 61% depending on how the event is detected or whether the aneurysm is ruptured or not. Some studies suggest that clipping of a ruptured aneurysm may be associated with a lower risk for developing shunt dependency, possibly through clot removal479; others do not observe a difference associated with technique. This increase in use of endovascular techniques is associated with a decrease in the overall number of adverse outcomes from treatment from 14. This is not cause and effect, however, because there have been advancements in other aspects of care and in both microsurgical and endovascular techniques. Hence the decision to use surgical or endovascular occlusion should be based on aneurysm morphology, patient age, and medical condition. In addition, decisions require a balance between the relative safeties of endovascular techniques versus the durability of microsurgical techniques. Hence surgical occlusion rather than endovascular occlusion may be preferred in younger patients because the degree of aneurysm occlusion, rate of aneurysm recurrence, and need for re-treatment are all less in surgical patients. The most frequent complications are thromboembolic events (10%) that may cause ischemic symptoms. In addition, not all aneurysms can be occluded, and over time there is a decrease of the occlusion rate in all sizes but most pronounced in giant aneurysms; on follow-up angiogram less than 70% of aneurysms remain completely occluded. However, the evolution of bypass procedures and flow diverters is improving the success of giant aneurysm treatment (see later). Nineteen post-procedural reruptures were identified and 58% of these patients died. The degree of aneurysm occlusion at initial treatment was associated with rehemorrhage and was greater in coiled (3. Instead, decision making is guided by retrospective or prospective clinical studies. The rates of morbidity and mortality in the endovascular group were less dependent on patient age than in the surgical group, suggesting that endovascular techniques may be better suited for older patients. This makes intuitive sense because the risk of nonocclusion and bleeding from a coiled aneurysm is greater than from a clipped aneurysm. The length of hospital stay was longer in the clipped population (median 4 days vs. When only death and discharge to long-term care were counted as adverse outcomes, there was no difference between clipping and coiling. On the basis of a four-level discharge status outcome scale (dead, long-term care, short-term rehabilitation, or discharge to home), coiled patients had a better discharge disposition.

The right recurrent laryngeal nerve exits the vagus nerve and loops below the right subclavian artery as it approaches the trachea and larynx medications held before dialysis buy cheap norpace 150mg line. Conse quently medicine ethics norpace 100 mg cheap, medial retraction of the trachea can cause ipsilateral paresis of the vocal cord treatment of chlamydia order norpace cheap. If the left side is exposed symptoms jaw bone cancer order norpace 150 mg on line, the thoracic duct is encountered as it arches from the side of the esophagus laterally to the angle between the internal jugular and subclavian veins medicine nobel prize 2015 buy generic norpace 150mg on line. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve can be retracted with greater ease because it loops around the aortic arch and approaches the trachea much lower medicine lake montana buy discount norpace. This feature distin guishes it from the thyrocervical trunk, which has multiple branches and exits from the anterosuperior surface. Alternatively, and more easily, the vertebral artery can be first located superiorly as it exits the transverse foramen of C6. The artery arises from the apex of two muscles as they attach to the carotid tuber cle: the anterior scalene muscle and the longus colli. The vertebral vein is formed at the lower end of the canal of the transverse foramina from a venous plexus within the canal around the vertebral artery. Care is taken to avoid destroying the sympathetic trunks and stellate or intermediate ganglia that lie on it. The proximal vertebral artery just above the stenosis is occluded with a hemoclip and cut. If the vertebral artery is not lax enough, it may be necessary to remove it from the C6 transverse process. With 70 monofilament nylon suture, the superior and inferior ends of the fishmouth opening are sutured to the corresponding ends of the hole in the carotid artery. One suture is used to form a running anastomosis on the back wall and is tied to the opposite end on completion. Before the last suture is tied, the lumens of both arteries are flushed with heparinized saline. After copious irrigation and hemostasis, the sternocleidomastoid muscle is reapproximated. A suction drain is placed in the neck for 24 hours, and the neck opening is closed in multilayers. The desired segment of the sub clavian artery is in the area of the anterior scalene muscle or more distally. A, Angiogram reveals severe stenosis (arrow) of the right vertebral artery origin (anteroposterior view). The patient underwent vertebral-carotid transposition with resolution of his symptoms. B, Postoperative angiogram (oblique view) reveals transposed vertebral (arrow) filling from the carotid injection. Although this procedure does not interrupt carotid blood flow, it requires two anastomoses and is timeconsuming. The vein is usually autogenous saphenous vein, although pros thetic materials have been used. Segmental resection and endtoend anastomosis can be used when obstruction is caused by entrapment,84 but the vertebral artery must be long and its diameter adequate. Surgery of the Second Vertebral Artery (V2) Segment the V2 segment of the vertebral artery is partially encased in a bony channel as it travels through the transverse foramina of the C1 through C6 cervical segments. Consequently, direct surgical reconstruction of the V2 artery is rarely undertaken. Most surgeons use angioplasty as the first choice of treatment for intrinsic stenotic lesions in the V2 segment, but extrinsic compression with osteo arthritic spurs is associated with excellent results from surgical decompression, as first reported by Hardin and colleagues8 and then in subsequent reports. Redundancy of the vertebral artery at the level of the cervical foramina can itself be a source of compression on cervical nerve roots, causing radiculopathy. Although subclavianvertebral endarterectomies have been used successfully since the 1960s, they are associated with several technical problems. The endarterectomy is a difficult approach to use with a lowlying subclavian artery. Diaz and coworkers89 reported surgical treatment (vertebral endarterectomy, vertebralto carotid transposition or grafting) in 11 of 12 patients with disease extending into the middle vertebral artery. The approaches to the V2 segment can be generally catego rized based on the necessity to expose the proximal (C6), middle (C25), or distal (C12) V2 segment, although the approaches can be extended as needed to encompass adjacent levels. The dissection would focus more superiorly in the deep fascial layer after the carotid has been dissected and retracted medially and the jugular laterally. When the tubercle of C6 is palpated, the insertions of the scalene and longus colli muscles are dissected subperiosteally, and the transverse process of C6 can be resected as needed to decompress the vertebral artery. Initially, a cervical radiograph is used to define the level of interest and should be repeated intraopera tively before the transverse process is drilled. The skin is retracted, and the platysma is left intact until it is completely exposed. This would be undertaken to decompress constriction of the artery at the level of the C6 foramen transversarium related to osteophytic bony compression or of fascial or ligamentous bands related to the insertion of the scalene muscles onto the transverse process of C6. A, the incision is placed along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. B, the skin is retracted, and the platysma is left intact initially until it is completely exposed. Then an incision is made longitudinally along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. C, By blunt dissection, a plane is developed between the strap muscles and the carotid sheath, trachea, and esophagus, which are retracted medially; the sternocleidomastoid muscle is retracted laterally. D, the prevertebral musculature is retracted after periosteal elevation, to expose the anterior tubercle of the transverse process, with the vertebra lying deep and medial in its bony canal. E, the vertebral artery is exposed by removing the bone surrounding the transverse foramen. Osteophytic compression of the vertebral artery can be similarly removed with rongeurs or drill. By blunt dissection, a plane is developed between the strap muscles and the carotid sheath, which contains the carotid, inter nal jugular vein, and vagus nerve. The prevertebral fascia is opened to expose the anterior longitudinal ligament and the longus colli muscles. The ligament is incised on its lateral border to allow a periosteal elevator to be used to mobilize the prevertebral musculature (the longus colli and longus capitis). Furthermore, dis section posterolaterally beyond the anterior tubercle must be avoided because this may lead to injury of the cervical nerve roots. The sympathetic ganglia lying on the lateral aspect of the longus colli need to be preserved. The bony canal of the vertebral artery lies just deep and medial to the anterior tubercle. Immediately below the transverse process, anterior to the vertebral artery, is the venous plexus, which is coagulated meticulously. Care is taken to preserve radic ulomedullary arteries that exit from the vertebral artery between C1 and C5 and supply the spinal cord. A posterior cervical approach can also be undertaken for decompression of vertebral artery loops but requires facetectomy and need for spinal instrumentation. Dissection of the overlying tissue reveals a venous plexus surrounding the vertebral artery. About 2 cm of vertebral artery can be exposed in the C12 intertransverse interspace. Further exposure can be obtained by removing the lateral wall of the transverse foramen of C1. DecompressionoftheV2Segment Several series have reported surgery in this segment of the ver tebral artery to treat external compressive lesions. ApproachtotheDistalV2Segment(C1-2) the approach to the distal V2 segment (C12) depends on the revascularization technique used. The incision is brought down to the platysma muscle, which is separated from the subcutaneous tissue. Along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the carotid sheath is entered, and the internal jugular vein is identified. The parotid gland is freed from the sternocleidomastoid muscle and deflected anteriorly. The location of the C1 tubercle can be confirmed by placing a clamp at this level and obtaining a lateral cervical radiograph. It is advisable to leave the occipital branch intact primarily because musculoskeletal branches from the occipital artery often feed the more distal vertebral artery. Anterolateral approach to the distal V2 segment, and venous graft from common carotid artery to vertebral artery. A, the incision is placed along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and extends posteriorly over the mastoid bone. B, the skin is retracted, and the platysma is cut, exposing the sternocleidomastoid muscle with the greater auricular nerve, which is also cut. C, the carotid sheath, including the carotid artery and jugular vein, is retracted medially, and the sternocleidomastoid is retracted laterally, to expose the levator scapulae muscle. F, the C2 ramus is cut and retracted anteriorly, revealing the vertebral artery with its surrounding plexus. H, Vein graft anastomosis is performed to the vertebral artery under temporary occlusion. I, After completion of the proximal anastomosis to the common carotid artery, vessel clamps are removed, establishing flow in the interposition venous graft. Angiography in a 77-year-old man with vertebrobasilar insufficiency demonstrated a hypoplastic left vertebral artery terminating in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery and a narrowed right vertebral artery with multisegmental stenosis at the origin and mid V2 segments, which was not amenable to endovascular treatment. Berguer and colleagues79 published the results from a large series of 100 distal vertebral artery reconstructions over a 14year period, performed ostensibly for ischemic symptoms. In the overall series, 16% of grafts failed in the early postoperative period, two symptomatically, and the patency rates were 75% and 70% at 5 and 10 years, respectively. More recently, this procedure has been used to create a conduit for endovascular access to treat complex posterior circulation aneurysms in patients with inaccessible or tortuous proximal vertebral anatomy. Synthetic grafts have also been used but have other disadvantages, including infection and pseudoaneu rysm formation. Furthermore, the use of synthetic grafts is limited over regions of constant movement because of rigidity and the corresponding wear caused by traction. Cadaver vein grafts offer another option, although longterm patency is not fully established. In the C12 interspace, a 2cm segment of vessel can be exposed without the need for bony removal and unroofing of the vertebral canal necessary in the mid V2 segment. Temporary clips are used to isolate the vertebral artery, and an incision is made sized to the fishmouthed end of the vein graft. If backflow through the graft is good, a temporary clip is used to occlude the vein. The donor vessel is cleared of any surrounding tissue, and a crossclamp is applied to its proximal and distal portions. Using an aortic punch, a 4 or 5mm elliptical arteriostomy is made in the wall of the donor. Angiography showing a vein graft (arrows) from the common carotid artery to the distal V2 segment. Surgery of the Third Vertebral Artery (V3) Segment the V3 segment is vulnerable to blunt trauma, and injury to the intima can result in thrombosis, embolization, and dissection. In many cases, if angiography reveals collaterals from the occipital artery, this artery is left intact. Before planning any type of procedure, surgeons must consider the biomechanics of the spine at this level. ApproachtotheV3Segment the V3 segment of the vertebral artery is best exposed through a posterior approach. The approach is more familiar to neurosurgeons because the patient is in a full prone or threequarter prone position. Similarly, the paraspinous muscles are dissected, exposing the lamina of C1 and C2 ipsilaterally, and the muscles retracted laterally. The artery is surrounded by a venous plexus, which must be dissected, main taining hemostasis with gentle packing and bipolar. The artery can be isolated over a longer segment by drilling the transverse foramen of C1 laterally to release and mobilize the vertebral artery. Frequently, muscular branches entering the vessel at the C1 level are present and should be preserved if possible. B, Exposure of the V3 segment within the sulcus arteriosus, with its surrounding venous plexus. Occasionally an anomalous vertebral artery can cause com pression on the spinal cord, leading to cervical myelopathy within this region. In younger patients, however, it is best to explore the anatomy and remove the compressive pathology. Attention must be given to allowing adequate redundancy to the occipital artery to avoid tension on the graft during head rotation, but at the same time avoiding kinking. Endarterectomy of the V3 segment for atherosclerotic disease is feasible through the same posterior approach, but with the advances in endovascular therapy, such an operation is primarily of historical interest. In the setting of more proximal vertebral occlusion, the occipital artery often provides collateral supply to the distal ver tebral artery, as previously noted.

Buy cheap norpace 150 mg. Dengue fever symptoms treatment pathophysiology and prevention.

Most of these conditions involve alterations in the physical properties of the vasculature treatment 5th finger fracture cheap 150mg norpace otc, the chemical properties of blood coagulation treatment pneumonia cheap norpace 100 mg visa, or the hemodynamic properties of blood flow symptoms 89 nissan pickup pcv valve bad 100 mg norpace fast delivery. The spectrum ranges from varying degrees of cerebral edema to massive hemorrhage and bilateral cerebral infarcts medicine x boston discount norpace 100mg without a prescription. Vascular injury and compression owing to trauma or mass lesions cause local endothelial damage and altered hemodynamics medications derived from plants cheap norpace 100mg without a prescription. In the largest study of cerebral venous thrombosis treatment brown recluse bite effective norpace 150mg, acquired prothrombotic condition was present in 34% of patients. Ehler and Courville36 found 16 cases of superior sagittal sinus thrombosis in a series of 12,500 autopsies. The most common locations for venous sinus thrombosis are the superior sagittal sinus and the transverse sinus. In the largest series of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the literature, superior sagittal sinus involvement was seen in 62% of patients, transverse sinus in 41% to 45% of patients, straight sinus in 18% of patients, and cavernous sinus in 1. When the thrombosis involves the deep venous system, the patient can exhibit akinetic mutism, coma, or decerebration. Cortical vein thrombosis without sinus involvement can present as a stroke syndrome. For example, a patient with visual alterations should be seen by an ophthalmologist. In all cases, imaging of the venous system is a cornerstone of diagnostic imaging work-up. Sometimes a dense triangle, also known as the delta sign, is seen as the thrombus occupies the superior sagittal sinus. The thrombus can be visualized directly, and cortical lesions, such as edema and hemorrhagic infarct, can be detected. T2- and T2*-weighted images are particularly helpful in early diagnosis,62 and susceptibility weighted imaging sequences for detecting hemorrhage. Papilledema is seen in approximately 50% of patients, and confusion, agitation, and other mental status changes occur in approximately 25% of patients. Although an acute presentation can mimic acute ischemic stroke, subacute presentations are more common. In 70% of patients, the complaints are present for days to weeks, and the symptoms can be fluctuating or progressive. The clinical presentation also varies according to the site and extent of thrombosis. When thrombosis is limited to the superior sagittal sinus or transverse sinus, the most frequent pattern of presentation is isolated intracranial hypertension. A number of patients with thrombosis are initially thought to have pseudotumor or idiopathic intracranial hypertension. If the thrombosis extends to the cortical veins, focal deficits and seizures can occur. False-positive identification can occur when sinuses are congenitally absent or hypoplastic. Falsenegative identification can occur when the signal of methemoglobin mimics that of flowing blood, when loss of signal occurs secondary to magnetic susceptibility artifact, or when the patient cannot cooperate and the study is technically poor. The typical finding is nonvisualization of all or part of a sinus during the venous phase of an angiogram. In cortical vein thrombosis, there is a sudden stop of the occluded vein, which may be surrounded by dilated collateral "corkscrew vessels. However, if anticoagulant treatment began at a later stage of the disease, no beneficial effect was found. For example, if an infectious process is identified, broad-spectrum antibiotics or drainage of purulent collections should be part of the treatment. Increased intracranial pressure can be treated with temporary short-term hyperventilation, osmotic agents (mannitol, hypertonic saline), drainage of cerebrospinal fluid via ventriculostomy or lumbar puncture, or surgical craniectomy. Systemic Thrombolytics Thrombolytic agents, such as streptokinase, urokinase, and tissue plasminogen activator, have been investigated in case reports and small series. Contraindications to thrombolytic therapy include recent childbirth, history of a bleeding diathesis, recent major surgery, recent major trauma, active gastrointestinal bleeding, or inflammatory bowel disease. It has been suggested that local infusion of thrombolytic agents with interventional neuroradiologic techniques can minimize the side effects seen with systemic thrombolytic therapy. Follow-up imaging demonstrated significant sinus recanalization, and the patient was left with only minor neurological deficits. In a randomized, placebo-controlled study with 20 patients, the group receiving heparin had a better outcome at 3 days, 8 days, and 3 months. Although their study failed to show statistical significance, there was a trend toward better clinical outcome in patients treated early with systemic anticoagulation. The findings of these prospective trials have been supported by a number of case series, which demonstrate that in most cases, Interventional Neuroradiology Recent advances in endovascular techniques not only enable the local delivery of thrombolytic agents to selective venous channels where the thrombus is located; they also allow for direct mechanical manipulation and removal of the clot. A variety of endovascular approaches have been reported, including local infusion of a thrombolytic, mechanical thrombectomy, and balloon angioplasty, indicating that there is still a need for better treatments for cases that are refractory to systemic anticoagulation. Routes of access include the transfemoral and transjugular routes and direct puncture of the dural sinuses. Urokinase was then infused at 4000 U/min for 3 hours and then 1000 U/min for 8 hours. The patient progressed from being unresponsive initially to having only a mild dysphasia at 4 weeks. These investigators successfully performed direct puncture of the superior sagittal sinus in a neonate and infused urokinase, resulting in clot lysis over 12 hours. Barnwell and coworkers89 reported direct transjugular endovascular thrombolytic therapy in three patients. All three patients had dural arteriovenous fistulas, and all three were treated by direct transjugular infusion of urokinase. In two patients, the clinical syndrome improved, with angiographic evidence of clot lysis and dural sinus recanalization. Smith and associates91 reported on seven patients with symptomatic dural sinus thrombosis who had failed a trial of medical treatment and treated with direct infusion of urokinase into the thrombosed sinus. The patients received urokinase doses ranging from 20,000 to 150,000 U/hr, with a mean infusion time of 163 hours (range, 88 to 244 hours). Patency of the affected dural sinus was achieved with anterograde flow in all patients. Six patients either improved neurologically over their pre-thrombolysis state or were healthy after thrombolysis. The only complications were an infected femoral access site and transient hematuria. A number of other small series confirmed the feasibility and efficacy of endovascular techniques for intrasinus thrombolysis. Currently, however, urokinase is not available in the United States; tissue plasminogen activator remains the only thrombolytic agent readily available. A continuous infusion was then started at 5 mg/hr until complete thrombolysis or 100 mg had been reached (mean total dose was 135 mg). A range of other treatment algorithms have been used with generally satisfactory rates of recanalization and clinical outcomes (see Table 374-2). Nine of the 10 patients receiving system anticoagulation had symptom-free recoveries; the 10th patient died from a severe intracranial hemorrhage. Seven patients underwent balloon thrombectomy after failing anticoagulation: three with symptom-free recovery, two with minor weakness, one with a gait disturbance, and one who developed a dural fistula. Eight patients went straight to endovascular thrombolytic therapy; five of these experienced a symptomfree recovery, and three patients had some mild weakness. Mechanical endovascular thrombectomy has also been used, through cannulation of the jugular vein or femoral access. Soleau and associates97 presented a small series of eight patients in whom a Fogarty catheter was used to pull thrombus down into the jugular access point in the presence of systemic heparinization. The AngioJet catheter was activated, and partial sinus thrombolysis was achieved using the hydrodynamic thrombolytic action of the catheter as it was slowly withdrawn to the jugular bulb. Generally, the stiffness of these rheolytic catheters confines their use to the dural sinuses. Endovascular therapy (either local infusion of thrombolytic or mechanical thrombectomy) can be achieved by transfemoral venous catheterization and cannulation of the cerebral venous system. This therapy is usually done after a diagnostic cerebral angiogram demonstrating venous thrombosis. A microcatheter is navigated to the venous channel where the clot resides, and a thrombolytic agent is infused at a predetermined rate. Either local thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy can be supplemented by placement of an intracranial venous stent. Although controversial, this stent has the potential to alleviate intracranial pressure gradient and potentially address both the thrombosis and the consequent elevated intracranial pressure. When medical therapy is inadequate and endovascular thrombectomy is not technically possible, there have been occasional circumstances in which the dural sinuses are directly punctured after craniotomy, and thrombectomy is performed at that time. An additional, albeit last-line, option remains open surgical removal of thrombus via open venotomy. Chahlavi and colleagues107 reported two cases in which the AngioJet was used successfully with direct transcranial puncture. There was insufficient evidence to support systemic or local thrombolysis, but it may be an option in patients on anticoagulation who deteriorate 3. A randomized trial with 300 patients would be necessary to confirm the treatment effect. Factors that suggest a bad prognosis are the presence of coma, extremes of age (high mortality in infants and in the elderly),56 site of thrombosis in the deep venous system or cerebellar system,110 severely increased intracranial pressure, and underlying sepsis or malignancy. Two patients who initially presented with isolated intracranial hypertension had blindness due to optic atrophy. One of the 51 patients with transverse sinus thrombosis developed a dural arteriovenous fistula. The frequency of long-standing epilepsy was low, suggesting that long-term anticonvulsant treatment is not necessary in most cases. All patients included in the study received system anticoagulation after diagnosis, typically with heparin. At this time point, 79% of patients had a modified Rankin Scale score of 1 or less, which is essentially a complete recovery. They identified various factors that were associated with worse outcome: male sex, age greater than 37 years, coma, mental status disorder, intracranial hemorrhage on admission, thrombosis involving the deep venous system, central nervous system infection, and malignancy. Seizures (10%) and new thrombotic events (4%) were the most frequent complications identified in this study. In their summation of the literature, 84% of patients had a good outcome and 12% died. Near to complete revascularization was achieved in 74% of cases, with 21% achieving partial, and 5% had no recanalization. New or increased intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 10%, with older technologies associated with poorer outcomes. A recent systematic review of case series and case reports in isolated cortical vein thrombosis included 47 studies with a total of 116 patients. Four percent of patients required decompressive craniectomy, and in-hospital mortality was 6%. Long-term changes in venous hemodynamics may lead to the development of collateral venous outflow channels. Extension of these channels to the external jugular venous system can lead to the development of dural arteriovenous fistulae. Approximately two thirds of patients recover rapidly without sequelae, particularly when the initial presentation is that of isolated intracranial hypertension. Recurrent seizures occur in less than 10% of cases, and only in patients who suffered seizures during the acute stage. Recurrence is especially prevalent when the patient has an underlying prothrombotic condition, but it occasionally occurs in the absence of a known cause. A high level of suspicion is necessary for clinicians to make an early diagnosis, although recent advances in diagnostic and therapeutic modalities have changed the detection and prognosis of this disease entity. Patients should then be bridged to long-term anticoagulation for 3 to 12 months based on associated risk factors. Additional multicenter studies will be necessary to determine the optimal medical therapy in light of the numerous new anticoagulation agents. Although the results are inconclusive, antithrombotic agents have been used with success to treat this condition. More recently, interventional neuroradiologic techniques have been used in refractory cases to deliver thrombolytic agents locally in a manner that is safe and, in most cases, effective for recanalization and clinical recovery. Endovascular techniques offer local delivery of thrombolytic agents and the option of mechanical thrombectomy; thus, superior clot lysis is achieved selectively in the venous sinuses, and system morbidity from hemorrhagic complications is minimized. These techniques are a viable option for cases that do not respond to systemic anticoagulation. Further study is indicated to better determine the overall efficacy and benefit of these treatment options. Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. A review of therapeutic strategies for the management of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Mechanical thrombectomy in cerebral venous thrombosis: systematic review of 185 cases. Study of the causes of visual failure before and after neurosurgical treatment in a series of 25 cases. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.

Focal adhesions are large medications list a-z purchase norpace in india, specialized treatment zinc toxicity buy 150mg norpace, dynamic structures in which actin filament bundles are anchored to transmembrane integrin receptors through an assembly of proteins crohns medications 6mp order 100mg norpace with mastercard. Integrins bind to extracellular proteins medicine 122 norpace 100 mg with visa, and within the cell medicine park oklahoma order norpace uk, the intracellular domain of integrins binds to the actin filament bundles via adapter proteins such as talin medicine 3605 cheap norpace 150mg overnight delivery, -actin, paxillin, and vinculin. In addition to anchoring the cell, focal adhesions function as signal carriers that can affect cellular behavior. Further evidence that cell adhesion plays a primary role comes from an intriguing Finnish study. Further investigation showed that two siblings had died of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Although no further genetic analysis was performed in this family, this specific translocation causes breakage of intron 1 of a splicing isoform of neurotrimin. The neurotrimin gene is expressed in the central nervous system and encodes a cell adhesion molecule. The many factors that may be involved in this process are known, but the exact sequence of events leading to aneurysm formation has been a mystery. Intracranial aneurysm formation is likely to result from many different initiating factors and pathophysiologic mechanisms; examples include focal hemodynamic injury, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Aneurysm growth occurs at region of low wall shear stress: patient-specific correlation of hemodynamics and growth in a longitudinal study. Remodeling of saccular cerebral artery aneurysm wall is associated with rupture: histological analysis of 24 unruptured and 42 ruptured cases. Some observations on reticular fibers in the media of the major cerebral arteries. Endothelial injury and inflammatory response induced by hemodynamic changes preceding intracranial aneurysm formation: experimental study in rats. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases expression in human cerebral ruptured and unruptured aneurysm. Network-based gene expression analysis of intracranial aneurysm tissue reveals role of antigen presenting cells. Involvement of mitogenactivated protein kinase signaling in growth and rupture of human intracranial aneurysms. Genomewide linkage in a large Caucasian family maps a new locus for intercranial aneurysms to chromosome 13q. Increased expression of phosphorylated c-Jun amino-terminal kinase and phosphorylated c-Jun in human cerebral aneurysms: role of the c-Jun amino-terminal kinase/cJun pathway in apoptosis of vascular walls. Multiple intracranial aneurysms in a defined population: prospective angiographic and clinical study. Predicting the risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms based on anatomical location. Medial collagen organization in human arteries of the heart and brain by polarized light microscopy. Interrelationships among wall structure, smooth muscle orientation, and contraction in human major cerebral arteries. Three-dimensional collagen organization of human brain arteries at different transmural pressures. Collagen biomechanics in cerebral arteries and bifurcations assessed by polarizing microscopy. Orientation of collagen in the tunica adventitia of the human cerebral artery measured with polarized light and the universal stage. Changes in collagen fibril diameters across artery walls including a correlation with glycosaminoglycan content. Effect of pressure on circumferential order of adventitial collagen in human brain arteries. Diverse effects of fibronectin and laminin on phenotypic properties of cultured arterial smooth muscle cells. Developmental regulation of the laminin 5 chain suggests a role in epithelial and endothelial cell maturation. Microscopic examinations of experimental aneurysms at the fenestration of the anterior cerebral artery in rats. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in human atherosclerotic and non-atherosclerotic cerebral aneurysms. Immunocytochemical studies of atherosclerotic lesions of cerebral berry aneurysms. Expression of structural proteins and angiogenic factors in normal arterial and unruptured and ruptured aneurysm walls. Complement activation associates with saccular cerebral artery aneurysm wall degeneration and rupture. A comparative study of patients without vascular diseases and those with ruptured berry aneurysms. Morphometric analysis of reticular and elastin fibers in the cerebral arteries of patients with intracranial aneurysms. Histological and morphometric observations on the reticular fibers in the arterial beds of patients with ruptured intracranial saccular aneurysms. Smooth muscle cells and the formation, degeneration, and rupture of saccular intracranial aneurysm wall-a review of current pathophysiological knowledge. Physical factors in the initiation, growth, and rupture of human intracranial saccular aneurysms. Elastin degradation in the superficial temporal arteries of patients with intracranial aneurysms reflects changes in plasma elastase. Serum elastase and alpha1-antitrypsin levels in patients with ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Apoptosis of medial smooth muscle cells in the development of saccular cerebral aneurysms in rats. Increased expression of phosphorylated c-Jun amino-terminal kinase and phosphorylated c-Jun in human cerebral aneurysms: role of the c-Jun aminoterminal kinase/c-Jun pathway in apoptosis of vascular walls. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in growth and rupture of human intracranial aneurysms. Cathepsin B, K, and S are expressed in cerebral aneurysms and promote the progression of cerebral aneurysms. Simvastatin suppresses the progression of experimentally induced cerebral aneurysms in rats. Macrophage-derived matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 promote the progression of cerebral aneurysms in rats. Prevention of rat cerebral aneurysm formation by inhibition of nitric oxide synthase. Mouse model of cerebral aneurysm: experimental induction by renal hypertension and local hemodynamic changes. Disruption of gene for inducible nitric oxide synthase reduces progression of cerebral aneurysms. Gene expression during the development of experimentally induced cerebral aneurysms. Association between semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase, a regulator of the glucose transporter, and elastic lamellae thinning during experimental cerebral aneurysm development: laboratory investigation. Velocity profile and wall shear stress of saccular aneurysms at the anterior communicating artery. Wall shear stress on ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms at the internal carotid artery. Regional accumulations of T cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells in the human atherosclerotic plaque. T lymphocytes from human atherosclerotic plaques recognize oxidized low density lipoprotein. Adventitial infiltrates associated with advanced atherosclerotic plaques: structural organization suggests generation of local humoral immune responses. Accumulation of activated mast cells in the shoulder region of human coronary atheroma, the predilection site of atheromatous rupture. Mast cells in neovascularized human coronary plaques store and secrete basic fibroblast growth factor, a potent angiogenic mediator. Co-accumulation of dendritic cells and natural killer T cells within rupture-prone regions in human atherosclerotic plaques. Colocalisation of intraplaque C reactive protein, complement, oxidised low density lipoprotein, and macrophages in stable and unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction. Association between complement factor H and proteoglycans in early human coronary atherosclerotic lesions: implications for local regulation of complement activation. Elevated levels of lipoprotein (a) in association with cerebrovascular saccular aneurysmal disease. Intra-aneurysmal hemodynamics in a large middle cerebral artery aneurysm with wall atherosclerosis. Genomewide linkage in a large Caucasian family maps a new locus for intracranial aneurysms to chromosome 13q. A balanced translocation truncates neurotrimin in a family with intracranial and thoracic aortic aneurysm. There are two important goals in the treatment of patients with intracranial aneurysms. In addition, the safety and efficacy of the treatment options and skill and experience of the practitioners need to be considered. The present chapter reviews the factors involved in decision making in the management of patients with cerebral aneurysms. Many patient-related factors will determine outcome irrespective of how the aneurysm is treated. Choosing the treatment modality that is safest and most efficient for each individual patient is an important therapeutic decision. This progress is reflected in the decreasing case fatality rate over recent years. By contrast, three quarters of the patients without postoperative neurological deterioration at 24 hours had a good outcome. This includes (1) patient age and comorbid conditions; (2) aneurysm morphology, lesion size, and attendant risk; (3) endovascular versus microsurgical accessibility/suitability, and long-term angiographic outcome; and (4) expected recovery duration and required longterm follow-up. Taken together, the natural history of the patient and the natural history of the particular aneurysm must be considered to determine the optimal approach to treatment. For example, the treatment of a small basilar bifurcation aneurysm in a 40-year-old will differ from that in an 80-year-old despite the similarity in the lesion. Thus exclusive focus on either the patient or the aneurysm is not an optimal management strategy. Patient considerations and the natural history of cerebral aneurysms are reviewed in Chapters 370 and 377. Furthermore, aneurysms that rupture may not be the same as the ones found incidentally. The reader is referred to Chapter 377 for a more detailed review, but a brief understanding of natural history is central to treatment decision making. Several risk factors are associated with development of intracranial aneurysms, including advanced age; hypertension; cigarette smoking; thoracic aortic aneurysms, especially descending ones; and hereditary deficiencies such as polycystic kidney disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, fibromuscular dysplasia, or a family history of aneurysm disease. To date, there have been no population-based clinical studies to examine the cost effectiveness of screening for intracranial aneurysms. Posterior aneurysm locations include the posterior circulation and posterior communicating artery. In carefully selected patients, flowdiverting stents may be used for complex aneurysms that recur after surgery. Raaymakers and coworkers47 also performed a meta-analysis from a Medline search between 1966 and 1996 and identified 61 studies involving 2460 patients. Morbidity rates were greater for large or posterior circulation aneurysms but also were greater in higher quality studies. Similar findings were reported from a Japanese natural history study that included 6697 aneurysms in 5720 patients. Increasing aneurysm size, location (posterior and anterior communicating arteries), and shape (irregular or daughter) were associated with increased risk. In 29,166 person-years of follow-up, mean observed 1-year risk of aneurysm rupture was 1. Other factors associated with increased risk of rupture include family history, high aspect ratio (dome/neck ratio >1. This may be important because several clinical series suggest that, even when a surgeon believes the operative result is satisfactory, vessel occlusion or aneurysm remnants may be found on 5% of postoperative angiograms. Furthermore, clip occlusion was achieved in 85% of lesions greater than 10 mm and 93% of lesions less than 10 mm. Reasonable surgical results can be expected with non-giant unruptured posterior circulation aneurysms. For example, we have observed a significant increase in surgical complications among posterior-oriented basilar bifurcation aneurysms. Calcification in the aneurysm neck often is associated with poor outcome, in part because many of these lesions are large or giant aneurysms. In addition, multiple clips frequently are necessary to occlude the aneurysm, leading to an increased incidence of cerebral embolism. Calcification may be removed by endarterectomy; despite this, surgical results remain poor because the remaining wall for clip placement is often very friable and thin.