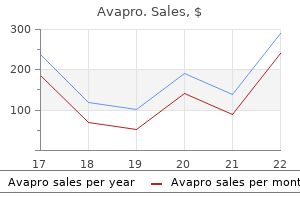

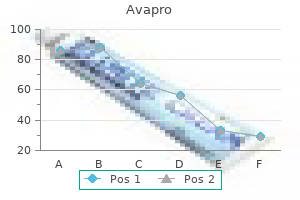

Avapro

Mohan S. Gundeti, MB, MS, DNBE, MCh (Urol), FEBU, FICS, FRCS (Urol), FEAPU

- Assistant Professor of Urology in Surgery and Pediatrics,

- The University of Chicago and Pritzker School of Medicine

- Director, Pediatric Urology, and Chief Pediatric Urologist,

- Comer Children? Hospital, the University of Chicago

- Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Sensory mapping confirmed a typical sloping dermatomal distribution of sensory changes and clinical quantitative sensory testing demonstrated positive phenomena (unexpected pain from pinprick and light touch) present at the distal end of the dermatome diabetes 1 symptoms purchase avapro cheap online. It is an opportunity for the patient to tell their story with pictures rather than words metabolic disorder multiple sclerosis purchase generic avapro line. When color is used diabetes medications glyburide side effects generic avapro 300 mg free shipping, for instance red for burning pain diabetes type 2 remission signs purchase avapro 150mg amex, blue for numbness diabetic leg ulcers buy avapro paypal, green for tingling diabetes type 1 in adults generic avapro 150mg mastercard, yellow for deep ache and black for stabbing pain, the picture can also provide important clues to the diagnosis. The value of a pain diagram A 58-year-old female developed a rash over her abdomen. The physician there diagnosed a the history should be reviewed along with the pain diagram to formulate a list of possible diagnoses. Then, the neurological examination will supplement additional information that will help formulate the diagnosis or differential diagnosis. Trying to determine the precise boundary of a dermatome (defined as the area of skin supplied by sensory neurons arising from a spinal nerve ganglia) underemphasizes how much overlap exists between two ganglia. A wide differential diagnosis should be formulated along with keeping an open mind to different possible conditions when evaluating the sensory maps. The health professional should not become excessively concerned if the lines do not perfectly resemble published diagrams of an innervated territory. Use one of these five coloring pens to shade the specific type of pain that you are experiencing. The value of additional neurological examination An elderly patient with mild dementia presented with left arm pain. The nursing notes documented pain when they touched the forearm but noted that her upper arm was normal. When assessed, she was asked about her sore arm, and surprisingly, she presented her right arm. Attempts to examine the left arm elicited cries of pain, leading to her withdrawing the left arm. After some cautious inspection, there were not any obvious abnormalities aside from tenderness over her entire left forearm. When she was asked again to indicate her painful arm, again she presented her right arm. This additional information helped to identify the neurological level of abnormality, since the picture of visuospatial neglect and diffuse pain in the same arm were suspicious for central mechanisms. In this case, conservative measures included advising the patient to avoid prolonged crouching or kneeling, avoidance of tight belts or clothing and weight loss to limit compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh. Sensory mapping Mapping of sensation can be performed with a brush or an unwound paperclip. The latter tool provides a stimulus of greater amplitude than a brush but less than that of a pin. It can be quickly dragged from normal skin to the described area of changes and will stimulate both small and large sensory fibers. An effective method is to start by establishing an area of normal touch sensation and then drag the paperclip towards the abnormal area in a radial pattern, establishing the boundaries of the sensory change. Concurrently, a pen can be used to draw reported sensory changes, easing documentation. Some clinicians will use photography to document the markings for later comparison and to aid in information transfer to other interested parties. However, the pain diagram suggested a lesion of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (meralgia paresthetica) due to the appearance of an oval patch at the anterolateral thigh inconsistent with that of the L2 dermatome. Sensory abnormalities were limited to that specific area, while further testing revealed that light brush sensation was reduced (brush hypoesthesia), pinprick was more painful than anticipated (pinprick hyperalgesia), and temperature sensations were described as delayed but normal in intensity. The remainder of the neurological exam confirmed a normal motor exam, normoreflexia (including at the left knee jerk) and unremarkable straight leg testing. Also, if a topical treatment was planned, the clinician may not want to attempt this should the affected area be significantly large. Bedside method for quantitative sensory pain testing Improving outcomes involves understanding disease risk factors and mechanisms, determining which are relevant, developing accurate and standardized measurements, and then developing and evaluating treatment interventions that address as many of the relevant contributing factors as possible. The evolution of assessment and treatment of hypertension is a model of this paradigm. One of the earliest developments that facilitated this evolution was the ability to accurately measure blood pressure. It began with the introduction of a standardized tool, the sphygmomanometer blood pressure cuff. Accurate and reproducible blood pressure measurement then allowed the development of standardized normal values. From there, deviations from normal could be quantified and tracked over time and as research developed new therapeutic interventions measuring treatment success became quantifiable. The ability to reliably reproduce these measurements was a crucial link between understanding disease mechanisms and improving treatment outcomes. In chronic pain states, the degree of peripheral damage or inflammation does not correlate well with pain severity. This initially led to a focus on the psychosocial aspects of pain to explain a discrepancy but over the last few years research has also focused on identifying the many different biological mechanisms that may contribute to chronic pain. For instance, a patient with osteoarthritis of the knee may also have some evidence of neuropathic pain and central sensitization. This is important information as it will potentially change the entire treatment paradigm for any individual. In the past, if central nervous system symptoms were present (such as fatigue, poor sleep, and pressure allodynia) clinicians tended to relate them to psychological mechanisms. Quantitative sensory testing is one tool that can help to determine the presence of different mechanisms in any given pain state. How it is used is evolving but like measuring blood pressure, its successful introduction as a clinical tool will require attention to detail to ensure the most accurate and reproducible results. The clinical role of bedside pain sensory testing in the diagnosis of neuropathic pain the Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group of the International Association for the Study of Pain recently published guidelines on the assessment of neuropathic pain [20]. The article stated "A careful bedside examination of somatosensory functions is recommended, including touch/vibration, cold, warmth and pain sensibility" for patients presenting with possible neuropathic pain. Sensory testing alone cannot determine the neuroaxial level of pathology, but documentation of sensory abnormalities will help to confirm or deny the presence of neuropathic pain. It also seeks to provide indirect information used to evaluate underlying sensory function abnormalities using only small, portable tools and with less time requirement than protocols developed by the German Neuropathic Research Network [23, 24]. Both protocols are psychophysical methods utilizing specific physical stimuli (pinprick, touch, vibration, heat, cold) to activate sensory receptors. Both protocols also require active participation and directed attention on behalf of the patient. Feedback to the authors is encouraged to improve the face validity of the procedures. Establish a control site where the patient does not describe any sensory abnormalities or pain and briefly examine to confirm the expected findings. If there are areas where sensation seems reduced or lost and others where there is hypersensitivity, ensure that you test at least one area that represents sensory deficit and one area that represents hypersensitivity. Begin a basic screening examination by testing touch (to evaluate the large A beta fibers) and then pinprick (to evaluate the small A delta fibers) to avoid sensitizing the skin. If these are normal, then vibration (which is also A beta) and temperature sensation (which is a mix of A delta and C fibers depending on the temperature tested) should be tested before you declare the sensory examination is normal. For instance, if the patient rates the stimulus to brush in the right hand as normal but reduced in the left hand, brush the normal right hand again and say, "If this is worth a dollar, (then brush the abnormal left hand) how much is this worth Likewise, a patient who reports a pinprick stimulus as 30/100 in the normal side and 80/100 on the affected side is also providing more information than "I feel it more. These include temperature differences between affected and unaffected areas which can be documented with a laser temperature probe. There may be differences in sweating in an affected body part or trophic changes such as with loss of hair, thinning skin, cracked dry skin, or altered nails. Secondary changes associated with chronic denervation, such as with Charcot neuropathic foot destruction with necrotic arthropathy and chronic ulcers on the plantar surface, should also be documented. The role of neural plasticity Injury to the nervous system results in maladaptive plasticity which can alter function at multiple levels of the somatosensory system including the peripheral 9 Section 1: the Clinical Presentation of Neuropathic Pain Table 1. Peripheral nerve injury can lead to increased neuronal activity throughout the central nervous system, resulting in increased responses to noxious and non-noxious stimuli. Sunburned shoulders are an example of normal, adaptive central sensitization not due to direct nerve injury, and anyone experiencing this will recall features of warm and pressure allodynia as they stood in a shower, for example. Under normal circumstances, this is a temporary phenomenon that may resolve as tissues heal. In some circumstances, however, either affected tissues fail to heal or the mechanisms evolve and, despite tissue healing, neuronal hyperexcitability persists, thus pain is no longer coupled to ongoing tissue damage. Documentation of this phenomenon is clinically important to provide (to patients, their family, insurance companies, and the courts), in the differential diagnosis, a physiological basis that may explain some of their symptoms. Diagnosis of peripheral sensitization relies on a history that has features consistent with neuropathic pain. Research has demonstrated some clinical findings that characterize plasticity at different levels or by different mechanisms but it can be difficult to impossible to separate peripheral from central mechanisms. In some cases this is because both mechanisms contribute to a particular clinical finding. For example, abnormally increased pain following a noxious cold stimulus (cold hyperalgesia) is mediated by peripheral sensitization in addition to reduced inhibition and central sensitization. In other cases peripheral input may be driving central sensitization so both will be present. Clinically, especially in the setting of a brief bedside examination, it can be difficult to document findings that would allow distinction between these two mechanisms. The bedside examination should focus on simply documenting signs consistent with the presence of sensitization. Interpretation of these signs must take into account caveats described at the end of this chapter. Repeated brush strokes (tested as one per second for 10 seconds) that produce increasing pain with each stroke is a simple test to perform. Repeated brush strokes or pinpricks (tested as 1 per second for 10 seconds) that produce increasing pain with each stroke is a simple test to perform. Have the patient rate the pain intensity at the beginning and end of the ten strokes/pinpricks and compare to the normal side. Repeated painful stimuli, like a pinprick, normally results in a progressively facilitated discharge by neurons in the spinal cord and results in an augmented pain response so that following repetitive pinpricks the intensity of the pain rating at the end is graded higher than a single stimulus. An exaggerated response to this test, compared to the normal side, is consistent with sensitization. Patients with nociceptive pain will also report brush and warm allodynia and heat hyperalgesia, such as is described with sunburn. Pressure allodynia, in particular, is common in both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Allodynia to brush, cold and heat and temporal summation to tactile stimuli, although not pathognomonic, are observed in a much higher frequency in patients with neuropathic pain [5,27]. Bilateral sensory changes can occur in neuropathic pain conditions regarded as unilateral. Conclusion the careful clinical evaluation of patients with possible neuropathic pain is extremely important. Although many neurological diagnoses now rely on sophisticated imaging or testing these modalities have a limited role in determining the presence of neuropathic pain. The tests may determine dysfunction but no test can demonstrate the presence or absence of pain. Improving neuropathy scores in type 2 diabetic patients using micronutrients supplementation. The prevalence and impact of chronic pain with neuropathic pain symptoms in the general population. Randomized control trial of topical clonidine for treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. New proposals for the international classification of diseases-11 revision of pain diagnoses. Quantitative sensory testing and mapping: a review of nonautomated quantitative methods for examination of the patient with neuropathic pain. Painful traumatic peripheral partial nerve injury-sensory dysfunction profiles comparing outcomes of bedside examination and quantitative sensory testing. Neurophysiology of pruritus: interaction of itch and 12 Name Date Please color the areas where you experience pain. Then circle with a pen all areas of pain and starting with the worst, number the areas in order of severity. In concert, these processes, amongst others, constitute the development of central sensitization. Increased neuronal excitability is often associated with voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVs). In these 50 m sections, epidermal nerve fibers (shown with thick arrows) appear green after immunohistochemical labeling. In diabetic peripheral neuropathy, numbers of epidermal nerve fibers diminish with extension of disease, contributing to sensory dysfunction. Skin lesions soon after rash healing surrounded by an area of anesthesia to punctate touch [solid line] and pin with wider area of pain on moving touch of cotton or tissue [interrupted line].

Diseases

- Dementia progressive lipomembranous polycysta

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Trichothiodystrophy sun sensitivity

- Brachydactylous dwarfism Mseleni type

- Arroyo Garcia Cimadevilla syndrome

- Englemann disease

The basal sweat output is recorded in the last minute of the 5-minute observation period on bilateral standardized sites on the upper and lower limbs diabetes type 1 patch purchase avapro 150 mg visa. It utilizes the normal physiological response of sweating which occurs with a rise in the core body temperature diabetes test panel order avapro 150mg with visa. The change in color of the red powder quinarizine on the moist skin signifies sweat production in normal areas diabetes type 1 left untreated order avapro visa. Computer scanning of the low or absent sweat areas is expressed as percentage of body surface diabetes diet underweight buy avapro on line. Distal hypohidrosis or anhidrosis is seen with peripheral neuropathies diabetic urine smell discount avapro 150mg without prescription, where global sweat abnormality is encountered with progressive autonomic failure or multiple system atrophy diabetes juvenile signs avapro 300 mg with mastercard. Vasomotor functions are based on normal physiological reflexes (baroreceptor and Bainbridge reflex) mediated by pressure receptors located in major vessels and lungs. The afferent signals are transmitted to the medulla, and the efferent reflex affects blood pressure and heart rate. These reflexes can be artificially stimulated by autonomic tests; deep breathing, Valsalva maneuver, and tilt test. The response of the cardiovascular system can be studied continuously by a non-invasive photoplethysmographic technique. The measurement of pulsatile blood flow should increase after the block due to vasodilation. The above-described tests are safe and reliable to screen for suspected peripheral neuropathy or to exclude associated conditions. Wider clinical applicability is limited due to the time and skill requirements, medications affecting results (opioids, tricyclic antidepressants), and artifacts due to pain-induced sweat production [16,34]. Conclusions Diagnostic testing for determining the sources of neuropathic pain has evolved over time. In concert with a good history and clinical examination, the selection of appropriate complementary testing will assist in the diagnosis in most cases. Assessment of the clinical relevance of quantitative sensory testing with Von Frey monofilaments in patients with allodynia and neuropathic pain. Usefulness and limitations of quantitative sensory testing: clinical and research application in neuropathic pain states. Can quantitative sensory testing predict the outcome of epidural steroid injections in sciatica Diagnostic validity of epidermal nerve fiber densities in painful sensory neuropathies. Differential impairment of the sudomotor and nociceptor axonreflex in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. This was due notably to the lack of validated operational diagnostic criteria for use in surveys to be used for the general population. Thus, the only available information was based upon retrospective studies in cohorts of patients seen at specialized centers and concerned with only specific etiologies. These studies allowed the characterization and estimation of the proportions of patients with neuropathic pain having specific etiologies and with assessment of their impact on quality of life (QoL). However, despite their scientific qualities, these studies did not permit the estimation for the overall prevalence of neuropathic pain in the general population. The situation has considerably evolved over the last few years, owing to the development and validation of screening tools in the form of simple questionnaires [25]. Several large epidemiological surveys using these screening tools have been carried out in different countries over the last few years. Estimation of the prevalence of neuropathic pain in the general population Two large population-based postal surveys have been carried out to estimate the overall prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. The prevalence of chronic pain (defined as pain or discomfort, either all the time or on and off for more than 3 months) Neuropathic Pain, ed. The patients with neuropathic characteristics were more likely to be female; they were also more likely to be unable to work due to illness disability, to have low educational qualifications, and to be smokers. Pain with neuropathic characteristics was more frequently located in the upper or lower limbs and had a higher severity score and longer duration than chronic pain without neuropathic characteristics. Its main objectives were the estimation of the prevalence of chronic pain with or without neuropathic characteristics in the general population and to compare the clinical and sociodemographic profiles of the participants reporting the two types of chronic pain [29]. This study consisted of a postal survey in a large representative sample of the French general population including more than 30 000 participants. The representativeness of the sample was verified on sex, age, education level, work, and region of habitation. In addition to socio-demographic information, the questionnaire mailed to the participants included 11 questions concerning pain. The first two questions were related to the identification of chronic pain (defined as daily pain for at least 3 months), whereas the other questions were related to the intensity, location, duration, and neuropathic characteristics of the more bothersome pain. Respondents with a total score 3 were considered to have neuropathic pain characteristics. Based on the analysis of the responses to the first two questions, our estimation of the overall prevalence of chronic pain was 31. Pain was of at least moderate intensity (4 out of 10) in more than 60% of the participants. Thus, the overall prevalence of chronic pain of moderate to severe intensity, which is clinically more relevant, was estimated to be 19. It was over twice more prevalent in manual workers or farmers than in managers and was more prevalent in rural areas than in large urban communities. Pain with neuropathic characteristics was more severe than chronic pain without neuropathic characteristics. Pain with neuropathic characteristics was more frequently located in the limbs whereas pain without neuropathic characteristics was more frequently located in the back. However, the vast majority of the patients (78%) reported more than one pain location. Interestingly, the more frequent locations in participants with neuropathic characteristics were the back plus at least one lower limb (46. Thus, despite the absence of a question related to the etiology of pain in the study questionnaire, the most frequently reported locations strongly suggest that the majority of pain with neuropathic characteristics corresponded to lumbar or cervical radiculopathies. Two other epidemiological surveys have been carried out more recently in Austria [31] and Canada [32], but, unfortunately, their results cannot be compared with those of the British and French studies, because of major methodological limitations. Other limitations of this internet survey are related to the lack of representativeness of the participants. The Canadian study [32] was a telephone survey of a random sample of 1200 households from the province of Alberta. The prevalence of chronic pain (defined as pain on a daily or near-daily basis) was 35%. In fact, such a high prevalence may reflect a major limitation in the design of this study. Limitations of the prevalence studies the similarities of the results of the two independent British and French surveys, using two different screening tools, tend to confirm their reliability. In addition, there are other more general limitations of these studies related to the difficulties associated with the definition and diagnosis of neuropathic pain. In principle, because of the lack of validated diagnostic criteria, one cannot equate the neuropathic characteristics identified in the present studies with neuropathic pain, as it has recently been redefined [33]. The new definition: "Pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system," restricts the neuropathic pain category to clearly defined neurological conditions. Thus, according to this definition, the identification of the underlying nerve lesion should precede the diagnosis of the type of pain. Identifying a neurological lesion requires a complete physical examination, often including electrophysiological testing, laboratory tests, and/or imaging, which are incompatible with large epidemiological studies. Incidence of neuropathic pain A study carried out in the Netherlands based on a general practice research database aimed to estimate the incidence of neuropathic pain [36]. According to this 1-year prospective longitudinal study, the annual incidence of neuropathic pain was 0. This study used a relatively large sample size (about 9000 participants) identified by a systematic search of computerized medical records, followed by a manual review. However, this sample of patients visiting their general practitioner was not representative of the general population. In contrast, the so-called "mixed" pain syndromes, including some of the most frequent causes of neuropathic pain, such as lumbar radiculopathies or cancer-related neuropathic pain, were not included in this estimation. Thus, it is likely that the overall incidence rate of neuropathic pain calculated by these authors probably corresponds to an underestimation. Impact of neuropathic pain on health-related quality of life the two large British [28] and French [29] surveys summarized above had both suggested that chronic neuropathic pain was more intense and more chronic. However, it could not be clearly determined in these studies whether the impact of neuropathic pain on quality of life is specifically related to its neuropathic origin. More recently, the British group [44] compared three subgroups of participants from their first survey [28]: a group of participants without chronic pain and participants with chronic pain with or without predominantly neuropathic origin. The second large epidemiological survey of the burden of illness due to chronic neuropathic pain was undertaken in the French general population [45]. Respondents with chronic pain were asked to locate their pain from a list of body sites grouped into seven categories, and to quantify the average intensity of their pain over the last 24 hours on numerical scales. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The location of pain and number of pain sites also differed between the pain groups: the proportion of respondents reporting pain in the lower or upper limbs was higher for those with neuropathic characteristics. These results highlight the fact that neuropathic pain has particular features, not only in terms of its underlying mechanisms, its clinical expression. This may reflect 27 Section 1: the Clinical Presentation of Neuropathic Pain Table 3. For sleep dimensions, lower scores for the first three dimensions indicate greater impairment; higher scores for the subsequent dimensions and global score indicate greater impairment. A significantly higher proportion of subjects with chronic pain and neuropathic characteristics than of subjects without neuropathic characteristics had visited a physician for their pain on a regular basis or were doing so at the time of the survey, and they also had visited a physician more recently. The number of specialists consulted was also higher for those with chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics. A significantly higher proportion of subjects with chronic pain and neuropathic characteristics than of those without neuropathic characteristics reported having used one or more drug treatment for their pain, and the mean number of drug treatments used for pain at the time of survey was also higher for those with chronic pain and neuropathic characteristics. Finally, a higher proportion of subjects with pain and neuropathic characteristics than of those without neuropathic characteristics were receiving analgesics, antidepressants, and antiepileptics at the time of the survey. In addition, large surveys have shown that all domains of quality of life, sleep duration, and quality and symptoms of depression and anxiety are consistently more impaired in subjects reporting chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics than in subjects reporting chronic pain without neuropathic characteristics. It has also been shown that 28 Chapter 3: Epidemiological considerations in neuropathic pain Table 3. These data, which should be interpreted with caution because of the "case definition" and "case ascertainment" issues related to neuropathic pain, will have to be confirmed in further studies. However, they strongly suggest that neuropathic pain is a specific clinical entity representing a significant disease and economic burden for the community. Patient perspective on herpes zoster and its complications: an observational prospective study in patients aged References 1. Prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia after a first episode of herpes zoster: prospective study with long term follow up. The prevalence, severity, and impact of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Chronic painful peripheral neuropathy in an urban community: a controlled comparison of people with and without diabetes. Pain and quality of life in the early stages after multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a 2-year longitudinal study. Pain report and the relationship of pain to physical factors in the first 6 months following spinal cord injury. First evidence of oncologic neuropathic pain prevalence after screening 8615 cancer patients. Neuropathic pain features in patients with bone metastases referred for palliative radiotherapy. Prevalence of self-reported neuropathic pain and impact on 30 Chapter 3: Epidemiological considerations in neuropathic pain quality of life: a prospective representative survey. Assessment of cancer pain: a prospective evaluation in 2266 cancer patients referred to a pain service. The burden of neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities. Cross-sectional evaluation of patient functioning and health-related quality of life in patients with neuropathic pain under standard care conditions. Clinical characteristics and pain management among patients with painful peripheral neuropathic disorders in general practice settings. Medication and treatment use in primary care patients with chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Better treatment of neuropathic pain will require a clearer understanding of its etiology and testing of pharmacological agents in such settings [3]. Several models have been developed in order to simulate particular aspects of human neuropathic pain and typically involve physical nerve trauma or the production of a disease state.

Order avapro cheap. CNN: sotomayor and diabetes.

Every person has a different perception of what is important to them in life and hence defines quality of life differently diabetes mellitus ulcers generic 150mg avapro amex. Quality of life is a multidimensional construct that includes biological metabolic disease 420 cheap 300 mg avapro with visa, psychological and social domains diabetes test non fasting discount 150mg avapro. The overall quality of life depends on various aspects hypo diabetes definition purchase avapro 150 mg fast delivery, including employment diabetic diet no no order 300 mg avapro amex, housing diabetes type 2 glucose levels discount avapro uk, neighborhood, cultural, and spiritual values of the Impact of chronic neuropathic pain on quality of life Pain is an individual experience, a subjective feeling that is difficult to measure. An extensive crosssectional survey of Finnish adults revealed chronic pain as an independent predictor of self-rated poor health [6]. Sometimes symptoms are cured, but the side effects of treatment significantly affect QoL. For example interventions for pain relief may produce drowsiness, nausea or memory impairment which may potentially impair physical and emotional function and exacerbate comorbid symptoms, which thereby offset the therapeutic benefit. Pain Physical functioning Emotional functioning Participant ratings of global improvement Symptoms and adverse events Participant disposition Enjoyment of life in general Fatigue Emotional well-being Weakness Staying asleep at night Other aspects of daily life such as travel and getting around in the community. Standardize outcome domains and encourage consideration of multiple relevant outcomes as opposed to single outcomes in clinical trials. Simplify the process of designing and reviewing research proposals, manuscripts, and published articles. Allow clinicians to make more informed clinical decisions for individual patients with respect to the risks and benefits. They recommended six core outcome domains for measuring the effectiveness and efficacy of treatment in chronic pain clinical trials (Table 28. This accounts for the aspects of health and well-being that are valued by the patient including physical, emotional, and cognitive function, and their ability to participate in meaningful activities with their family. Phase 1 of the study identified 19 outcome domains with significant impact on chronic pain conditions that were viewed as more important by patients in evaluating the effectiveness of treatment. Phase 2 was conducted to examine the importance and relevance of the identified domains. The domains that were scored as highly important to patients are listed in Table 28. This emphasizes the importance of assessing the patient with chronic pain and not the pain in isolation. Neuropathic pain-specific outcome domains It has been over a decade since the research suggested that neuropathic pain affects quality of life. The important outcome domains for these patients differ depending on the pain condition they suffer from. Primary domains (physical functioning, sleep quality or interference, and emotional functioning). Supplemental domains (role functioning, including work, educational activities, and social functioning). In patients with trigeminal neuralgia there is significant impairment of daily living and health status, especially general activity and mood. Pain severity is directly associated with greater interference in daily activity [18]. Greater disability is seen in people who perceive themselves as disabled, dependent on medication, the healthcare system, and other external factors for control of pain. Post-herpetic itch causes unpleasant sensations and the disruptive need to scratch leading to substantial disability. In rare cases the combination of chronic pruritus and profound sensory loss after herpes zoster (shingles) leads to severe self-injury [24]. Pain experienced by these patients is central neuropathic or nociceptive pain [26] and associated with motor and sensory dysfunction. Evidence suggests that when this pain becomes persistent or severe it may produce exhaustion and fatigue. Economic status has an impact on quality of life in stroke patients with low QoL scores being seen more frequently in low compared with high economic groups [33]. Whenever an individual faces pain or fear of pain they respond in either a positive or negative fashion. Passive responders feel hopeless and vulnerable due to lack of control over the threat and present with greater disability and distress. Active responders feel more control over the situation, adjust more effectively and show improved functional and physical fitness. Patients with spinal cord injury who respond by "guarding" (limiting activity in painful body parts) and depend on assistance in response to pain suffer from greater pain intensity, pain interference, and disability. Positive coping responses such as task persistence, distraction, and positive self-talk, result in better functional outcomes and lower pain intensity [19]. Catastrophizing Catastrophizing is an irrational thinking of beliefs that something is far worse than it actually is [35]. An example could be that a student sitting an examination gets preoccupied with thoughts of failing and consequently fails the exam. Case scenarios in chronic pain patients include thoughts such as "I may end up paralyzed" or "I may become completely disabled. Fearavoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Catastrophizers dwell on the most extreme, negative consequences of pain and interpret pain as extremely threatening. This intense pain experience is then perceived as harmful and damaging to the body. All attention is directed to pain, causing interruptions in ongoing activities, resulting in subsequent activity intolerance and increasing disability. Catastrophizers find it difficult to disengage from pain cues, leading to hypervigilance. The brain imaging of high-level catastrophizers showed decreased activity in the prefrontal cortical region which is involved in top-down modulation of pain [36], which helps explain why these people dwell on their pain experience and find it difficult to disengage from it. A volunteer study of pain intensity involved testing a cold metal bar to the neck [40]. One group were made to believe that a cold metal bar was hot, the other group believed the same metal bar was cold. The group believing the bar to be hot rated it more painful than the group who believed it to be cold. Several studies have demonstrated association of higher levels of catastrophizing with reduced tolerance and higher pain ratings [37,38]. Catastrophizing contributes independently to the development of phantom limb pain in amputees [41]. Anticipation, involving the dorsal anterior cingulated gyrus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Heightening emotional response to pain involving the claustram which is closely related to the amygdala. An important clinical implication of this relationship between pain and catastrophizing lies in understanding that there are factors other than tissue damage or nociception which may contribute to higher ratings of pain intensity. When acute pain is perceived as nonthreatening, the patient continues with their daily activities. In the long term, chronic disuse leads to disability and in turn, leads to depression. Depressed mood increases the unpleasantness of pain and catastrophizing and becomes a vicious cycle. This emphasizes the need to assess all aspects of pain and its effect on quality of life if an effective management plan is to be formulated. Patients with trigeminal neuralgia reported a pain-associated impact on employment in 34% of cases. This took the form of a reduction of scheduled work time (days missed), disability, unemployment, or early retirement. In patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in a community-based clinic, over 60% reported moderate or severe interference in performing all activities except their relations with others [14]. Chronic neuropathic pain is associated with alterations in physical and psychological functioning [6]. It is associated with more intense pain compared with other types of pain and has a significant impact on QoL. With an aging population, it is assumed that the prevalence of chronic neuropathic pain will increase in the future. Prevalence of diabetes is expected to double over the next two decades and hence the prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy is expected to increase [44]. As discussed above, depression, catastrophizing, poor coping skills, and anxiety all play a role in the development and maintenance of chronic neuropathic pain. It is important to understand the predictors for chronic neuropathic pain and their assessment in addition to pain relief. This will enhance timely identification of at-risk patients, promoting prompt preventive measures and intensive management of these patients to reduce their burden of chronic neuropathic pain. Treatment for pain reduction is not always associated with improvement in function or satisfaction. It is important to consider psychosocial treatment geared towards physical, emotional, and social functioning. Such interventions provide patients with a sense of control over their pain and address the sense of helplessness. For example, improving sleep or emotional functioning in patients with neuropathic pain may benefit or enhance physical functioning, the central theme being identification of outcome domains that are clinically meaningful to patients, providing a comprehensive efficient evaluation of treatment response. This highlights the importance of psychological factors in understanding chronic neuropathic pain and Health-related QoL in cancer patients Compared with other neuropathic pain conditions cancer patients with neuropathic pain are in a different category. Bony metastasis is common and may lead to bony invasion and fracture or direct invasion of local tissues including peripheral or central nervous tissue. It is highly debilitating, and the associated pain is difficult to manage and limits daily activity with a significant impact on QoL. Loss of independence, financial pressures, and strained relationships all contribute to depressive symptoms in cancer patients. There is no difference in depressive symptomatology suffered by cancer patients with or without neuropathic pain. Neuropathic cancer pain has been reported to cause more pain interference with general activity, walking ability, normal work, sleep, relationships, and mood. It involves assessing and targeting biological, psychological, and social aspects of pain. In cancer patients, assessment of the spiritual aspect is important with the biopsycho-social assessment. Patient burden of trigeminal neuralgia: results from a crosssectional survey of health state impairment and treatment. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in spinal cord injury: replication and cross-validation. Catastrophizing is associated with pain intensity, psychological distress, and pain-related disability among individuals with chronic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Pain, medication use, and health-related quality of life in older persons with post-herpetic neuralgia: results from a population-based survey. Intractable postherpetic itch and cutaneous deafferentation after facial shingles. Individualized functional priority approach to the assessment of health related quality of life in rheumatology. Severity in diabetic peripheral neuropathy is associated with patient functioning, symptom levels of anxiety and depression, and sleep. Classification of mild, moderate and severe pain due to diabetic peripheral neuropathy based on levels of functional disability. Painful diabetic polyneuropathy: epidemiology, pain description, and quality of life. Differences in cognitive coping strategies among pain-sensitive and paintolerant individuals on the cold-pressor test. Cognitive-emotional sensitization contributes to wind up like pain in phantom limb patients. Fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. Pain, neuropathic symptoms, and physical and mental well-being in persons with cancer. Preoperative predictors of moderate to intense acute postoperative pain in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Hutchinson Chronic pain is a complicated, multifaceted disease process affecting millions of people worldwide. Critically, the somatosensory system has previously been thought to consist merely of neuronal networks, and it was believed that the dysregulation of this "wiring" led to the chronic pain pathologies. However, data developed during the past two decades has shed light on neuronal and non-neuronal origins of neuropathic pain [2]. Despite many preclinical and clinical advances the precise mechanisms underlying neuropathic pain are still not well understood and the efficacy of current pharmacological therapies is at present symptomatically suppressive, rather than disease modifying or curative.

Nymphaea maximilianii (American White Pond Lily). Avapro.

- Chronic diarrhea, vaginal conditions, diseases of the throat and mouth, and healing burns and boils.

- Are there safety concerns?

- What is American White Pond Lily?

- How does American White Pond Lily work?

- Dosing considerations for American White Pond Lily.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96302